Prelude

I remember waiting for the ISS as night fell. Standing next to a lake just after sunset, waiting for that little fleck of light to come over the horizon. For a few moments as it passed overhead, the astronauts aboard were no farther away than my grandparents, a few states over. But this proximity was fleeting; moving at over 17,000 mph, it rapidly dimmed, and disappeared over the horizon, daring me to meet it again another night.

How to find it? There were, and are, quite a few excellent sites that will predict visible passes of the ISS and other satellites. But the process was always opaque and mysterious to me. You put in your current location, and it tells you, to the nearest second, when it will appear, and without fail, it always does.

A few years ago, I set out to learn how this process works, and finding a lack of quality explanations, decided to document it myself. This is the beginning of that journey. I hope you’ll join me as we attempt to build a minimal satellite tracker.

Technical Prerequisites

I’ll be writing this project in python, and posting code to a GitHub repository. I recommend you install Python locally, so you can follow along easily. If you’re familiar with setting up a development environment, you can safely skip this portion. Otherwise, the easiest way to get up and running is to go install Anaconda. Make sure you install Python 3. I’m going to assume a knowledge of very basic programming, or the ability to read python.

Orbital Mechanics Prerequisites

There’s quite a few concepts that are essential to understanding how to predict orbits. I’m going to touch on the most important ones, and provide links to Wikipedia and other references for more details. I’m also going to skip the derivations of several formulas, because other, much more skilled authors have done a better job than I can. However, I’m going to assume a knowledge of basic physics, derivative calculus, and linear algebra. If you’re not comfortable with any of these, go check out Khan Academy and/or MIT OpenCourseWare. They’re both great and have helped me a lot.

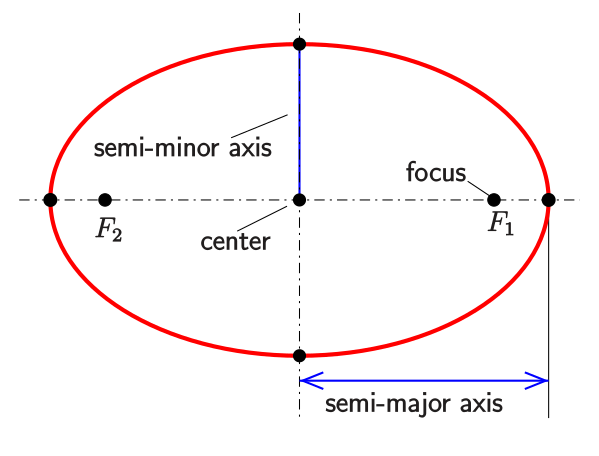

Ellipses

Ellipses are curves that surround two focal points, such that for each point on the curve, the sum of the distances to the two focal points is constant. You might know them as ovals. We’ll use them to model the path an orbiting object makes around its attractive body. The short “radius” is the semi-minor axis, and the long “radius” is the semi-major axis. We represent how “squished” the ellipse is with a dimensionless quantity called eccentricity, which is defined as \(\sqrt{1 - \frac{b^2}{a^2}}\) where a is the semi-major axis, and b is the semi-minor axis. In the case of a circle, a = b, so the eccentricity is 0.

Orbital Anomalies: Mean, Eccentric and True

Houston, we’ve had a problem! Just kidding! Orbital anomalies aren’t something to be worried about, they’re simply a way to measure where in its orbit an object is. We measure orbital anomalies as an angle from the pericenter (also called a perigee in the case of Earth-centered systems), which is just the closest point of an orbit to its body. Most orbits are elliptical, so they move closer and further from the object they’re orbiting.

Let’s say a satellite takes 100 minutes to complete one orbit. If the orbit is perfectly circular, its speed is constant, and after 50 minutes, it moves 180 degrees around its orbit. But if it’s elliptical, then it may have moved more or less than 180 degrees, since its speed fluctuates over the course of the orbit.

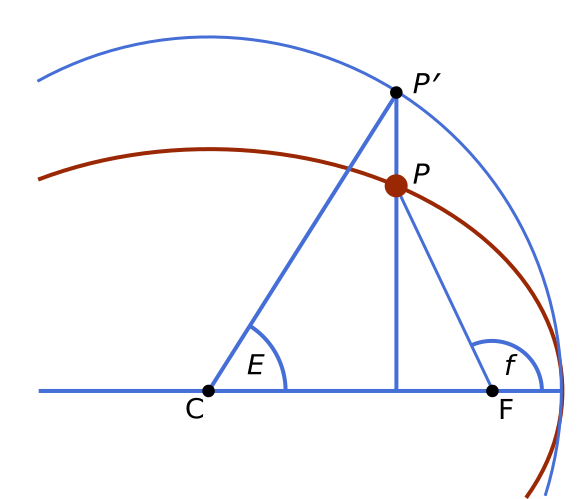

It’s also important to know that the orbital period of an elliptical orbit is determined only by the size of its semi-major axis (see Kepler’s third law, below). This means that a circular orbit of the same radius as the semi-major axis will have the same period as its elliptical counterpart. Thus, on average, the angular velocities are the same. Because of this, we call the anomaly of the imaginary circular orbit the Mean anomaly. Since an object in circular orbit has a constant speed, we can easily determine its position, by multiplying speed and time.

The actual position in orbit (with respect to the center of the imaginary circular orbit) is called the Eccentric Anomaly, which is represented by the angle E in the diagram above. This does not necessarily increase at a constant rate, as the Mean Anomaly does, but it lets us determine the true position of the satellite in its orbit. In the case of a circular orbit, the Eccentric Anomaly is equal to the True Anomaly, which is the angle from the pericenter to the object, as observed from the focus, shown as angle f above. However, in an elliptical orbit, the foci are not at the center of the imaginary circle, so the True Anomaly differs from the Eccentric Anomaly, as in the diagram above. In the case of determining the position of a satellite orbiting the Earth, we need to use the True Anomaly.

How do we find the True Anomaly from the Mean Anomaly? Read on!

Kepler’s Equation

You may have heard of Johannes Kepler and his three laws in school. We’ll be using all of them in this project. For reference, they are:

- All planets move in elliptical orbits, with their attracting body at one focus

- A line that connects a satellite to its body sweeps out equal areas in equal times

- The square of the period of any satellite is proportional to the cube of its semi-major axis

For now, let’s talk about the second law. From this law, and using a little geometry and trigonometry, we can derive the following equation: \[ M = E - e \sin{E} \] This is known as Kepler’s Equation. \(M\) is the Mean Anomaly, \(E\) is the Eccentric Anomaly and \(e\) is the eccentricity. If you know the Mean Anomaly and eccentricity, then you can compute the Eccentric Anomaly and find out the real position of the satellite.

For more information on how this is derived, see Fundamentals of Astrodynamics by Bate and Mueller, Chapter 4. PDFs may be available online.

Given the Eccentric anomaly, we can find the True anomaly with a little trigonometry. As we’ll see in the next part, we don’t need to compute the True Anomaly directly, instead, we can use the parametric equations for an ellipse given the Eccentric Anomaly: \[x = a(\cos{E} - e)\] \[y = b\sin{E}\]

Keplerian Elements

The same way that a point in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) (3-D space) can be described with three Cartesian coordinates, an orbit can be described with the following Keplerian elements:

- Eccentricity (\(e\))

- Semi-major Axis (\(a\))

- Inclination (\(i\))

- Longitude of the Ascending Node (\(\Omega\))

- Argument of periapsis (\(\omega\))

- True anomaly (\(\theta\)) at epoch (\(M_0\))

We’ve already discussed eccentricity and the semi-major axis, so let’s discuss the remaining four.

The inclination of an orbit is the angle it makes with the equator as it crosses it. An orbit that goes over both the north and south poles, called a polar orbit, has an inclination of 90 degrees, since it crosses the equator at a perpendicular angle.

We measure positions on the surface of Earth, a near sphere, using latitude and longitude. We can also measure position on the celestial sphere using Right Ascension (analogous to longitude) and Declination (analogous to latitude). Right Ascension (RA) is measured eastwards from the First Point of Ares The ascending node of an orbit is the point where it crosses the equator going from the southern hemisphere to the northern. The Longitude of the Ascending Node, also called the Right Ascension of the Ascending Node (RAAN) is the Right Ascension on the celestial sphere of this point. We measure it this way because the celestial sphere, unlike the earth does not rotate.

The Argument of periapsis is the angle from this ascending node to the point where object reaches perigee (its closest point to Earth). You’ll remember from above that orbital anomalies are measured from perigee, making this an important value for orienting the orbit in space.

Finally, the epoch is a certain time at which the Keplerian elements were measured, and the true anomaly is the angle from the perigee at that exact moment.

Together, these parameters fully define an orbit, and allow us to predict the position of a satellite at any point in the future.

Astronomical Time: Julian Dates and Sidereal Time

Calendars are complicated. Some years (leap years) have an extra day in February to keep everything aligned, not to mention various changes in calendars over the centuries. To keep everything simple(er), astronomers use the Julian date to tell time. It’s the number of fractional solar days since midnight on Monday, January 1, 4713 BC. Why did they pick this date? It so happens it’s the starting point of several astronomical cycles, and precedes all recorded history, so it’s a convenient zero point. As I write this, the current Julian Date in UTC is 2458693.12131.

We already talked about coordinates in the celestial sphere (Right Ascension and Declination). Since the earth rotates beneath the celestial sphere, you can actually use your Right Ascension to tell time. This is called Sidereal time. If the current sidereal time is 14:15, and I look due north, I’ll see stars at Right Ascension 14h15m. Sidereal time will come in handy later when we attempt to convert celestial coordinates to terrestrial ones.

Whew! That was a lot of information. Don’t worry if you didn’t get it all, it will become clearer as we apply these concepts to orbit prediction. In the next post, we’ll use these concepts to find the current latitude and longitude of the ISS. Stay tuned!